Hey I just met you

The Network’s laggy

But here’s my data

So store it maybe

– Carley Rae Jepsen and the Perils of Network Partitions

Hey Guys and Gals hope you’re doing great! So I have been reading this book (Designing Data-intensive Applications) for ages and I thought we should talk about one of the chapters in this Blog. The Book has been amazing and super fun to read. Some of the cool parts are straight out of the book, Hope you enjoy it!

Remember the simpler times when everything about an application lived on a single machine. The sweet breezy days not having to worry about syncing database replicas, running around the offices looking for the faulty switch and times when someone power cycled the wrong device. Things were easy, you knew which device to reboot since there was only one. I’m kidding!!

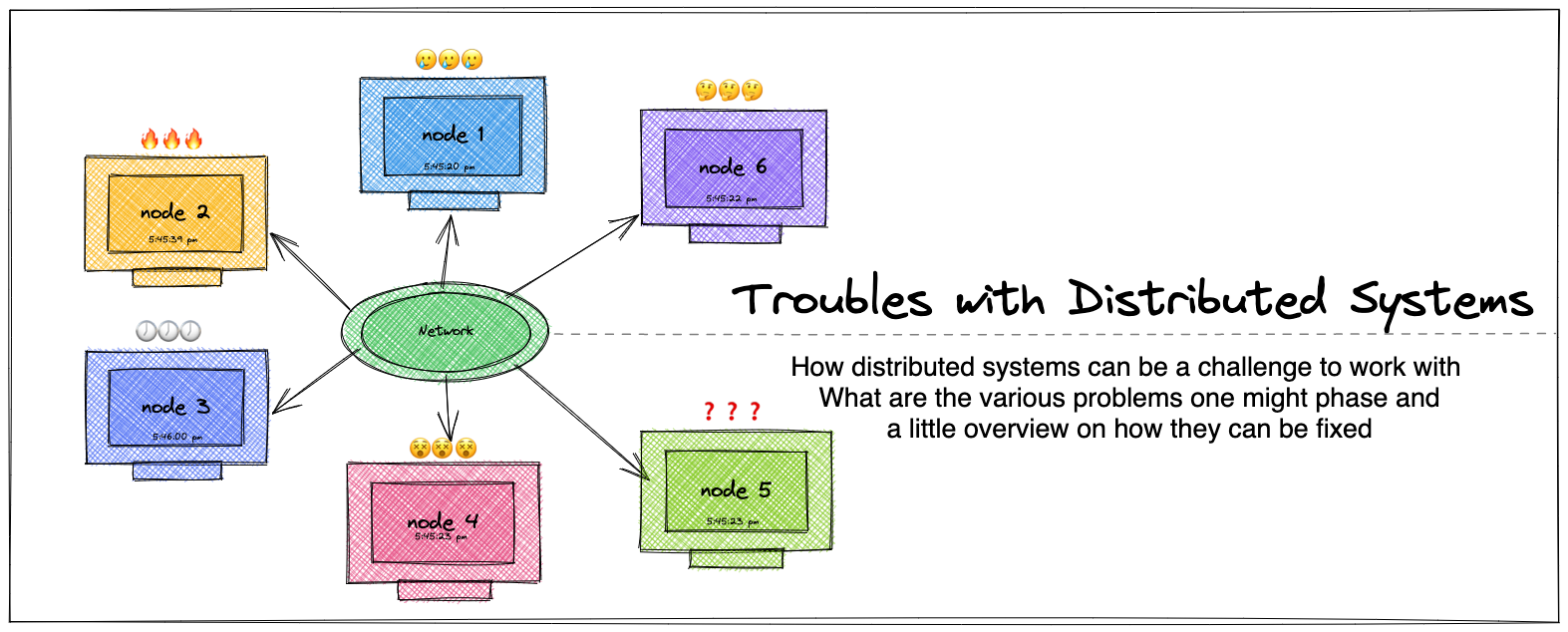

Although the central architecture come with flaws, but these flaws are simpler to understand and rather easy to fix. When the infrastructures grow, the need for distribution is obvious. We would not want to depend on a single server so we have multiple server nodes in place. If one of them dies, there are other nodes that will take up the load and distribute it among the available ones. What if the geographic area is affected by a natural calamity? To avoid it from affecting all of our operations, we keep the nodes geographically apart.

When it comes to databases, data is the king right. To avoid losing data at any point, we replicate the database and maintain a Write replica (leader) and multiple read replicas. The write replica only handles the expensive operations like writing and updating the database. On the other hand, Read replicas are responsible for querying the database. The replicas sync in real time to keep the data consistent. In case of fault when the write replica is down, one of the read replicas must be elected as the leader. The inconsistency in network can make it hard to determine whether the leader is actually down. Choosing a new leader could happen with an election process where the replica with most up-to-date changes becomes the new leader. Then we must reconfigure the system to use the new leader while also making sure when the old leader comes back, it becomes a follower and recognise the new leader.

To distribute load evenly across servers (so no one server gets too many requests at any point) and keep the servers safe from external attacks, we use a load balancer which is a yet another component being added to our infrastructure. In case of fault or a node failure, we also have to make sure that load balancer doesn’t send the requests to the faulty server node. This doesn’t end here, we also have cache to make the transaction snappy and avoid the unnecessary load on database. We introduce CMS to take care of our static content and the list goes on and so does the list of possible faults that come with additional tools.

A distributed architecture is one that isolates different units so as to avoid a total blackout. We introduce new tools to solve problems without realising that we are also introducing more Points of Failure(POF). We must not resort to tools to solve every one of our problems at least until we haven’t fully understand why the problem exists in first place.

Few potential problems with distributed systems:

Partial Failures :

Partial failure is when a part of infrastructure is faulty while other parts of system are unaffected by it. In distributed system where the infrastructure is made up of many server nodes, it is often difficult to determine the root of the fault. The solution you apply might work sometimes but might fail miserably other times. This indeterministic nature of faults makes the distributed systems difficult to work with

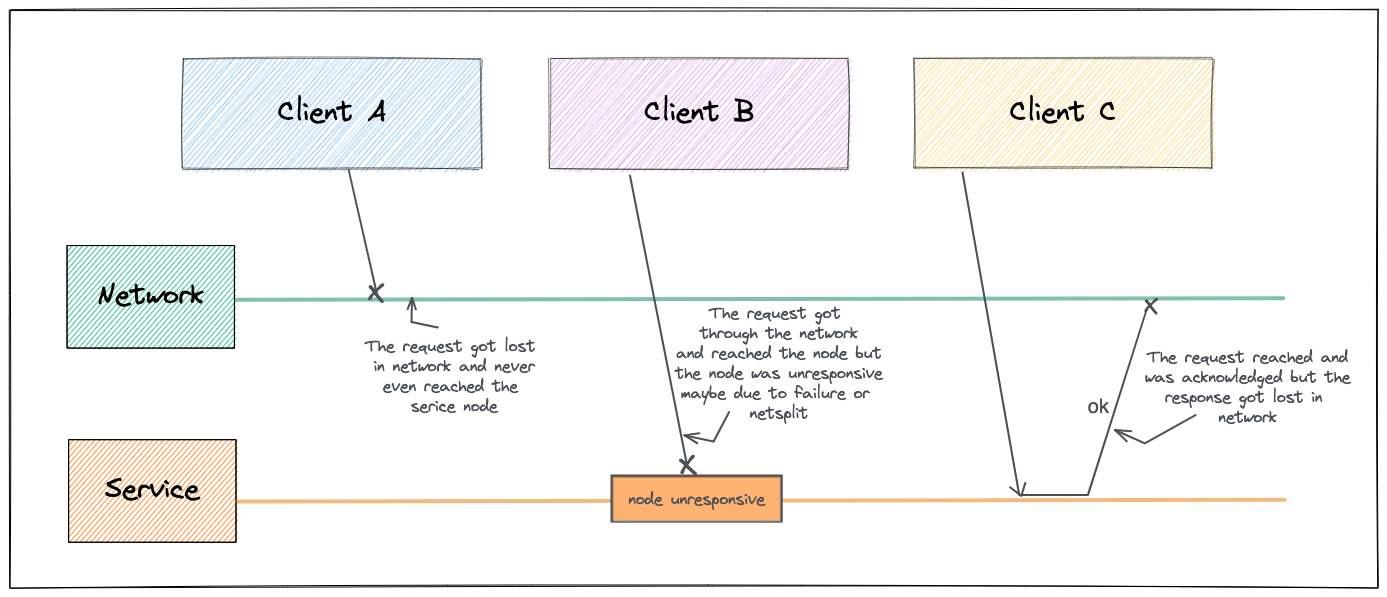

Network Calls /Unreliable Networks:

Sometimes, you might not even know if the solution worked due to a delay in network call or a possible network partition. Distributed systems are nothing but a bunch of machines connected by a network. This network is the only way the machines can communicate with each other. The way internet (and most internal networks) works is when a machine sends a message to another machine, the network doesn’t give a guarantee as to when the message will reach the other party or even if the message will reach at all. There are several thing that can go wrong with network:

- Your request never reached the target machine

- The request is waiting in the queue since the target machine is overloaded

- The request did reach but the response got lost in the network

A reason why the request never reached the target machine could be due to Network Partitions. A Network Partition or netsplit is a situation when a part of network is cut off from rest of the network due to network failure.

Even if network faults are rare in your environment you should still prepare your software to handle it. Because if the software is not made aware of or tested against such faults, it might do arbitrary unexpected things when a network call fails. It might not necessarily mean that you must tolerate the network faults, it can be as simple as showing an error message or temporarily pause serving.

To solve the problems with network calls, the simplest way is to use timeouts. For example, if a node doesn’t respond in a certain amount of time. It will be declared dead. But with timeouts comes problem of deciding how long a timeout should be? a long timeout means the user will have to wait for a longtime or see loading messages only to find out the request has failed. On the other hand a short timeout can declare a node dead prematurely only to find out that the node was actually loaded and took time to respond, in this case the operation might end up being performed twice. Or the worst case with short timeouts, every node starts declaring every other node dead and everything stops working all together.

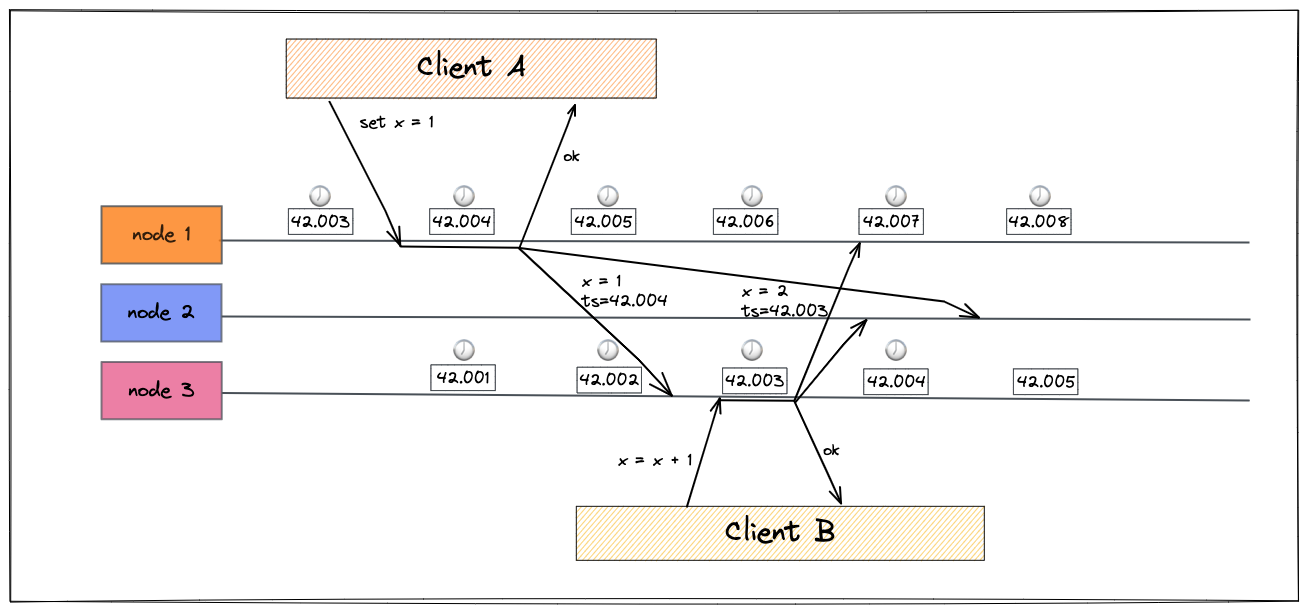

Unreliable Clocks

Its crazy how clocks can cause so much pain in a distributed systems architecture. I mean who would think or start the troubleshooting with clocks for a broken/malfunctioning distributed system. Clocks play an important role and are easy to mess up. a few milliseconds up or down is enough to make your app do weird things. Applications depend on clocks to answer many questions like:

- Has the request timed out yet?

- How many queries per second did a service handle on average in last hour?

- When was the article published?

- At what time should the emails be sent out?

- What is the timestamp on error message on the log file?

The clocks must be synchronised across the system to calculate everything correctly. NTP is usually used to sync the time across the network. When a system has strayed a little too far from NTP servers, it may refuse to sync or forcibly reset the local time to match with NTP. In later case the services observing time might see the time go backward or suddenly jump forward.

In the above diagram, 2 clients are trying to modify the value of variable x. The clocks are out of sync by mere 3 milliseconds which is better than what we can expect in practice. Client A’s write operation ( x=1 ) has a timestamp of 42.004 and Client B tries to increament x by 1 ( making it x=2) with timestamp of 42.003, when both of these transactions reach node 2, the client B’s increment transation will be ignored since the most recent transation as per timestamps is x=1 at 42.004. This conflict resolution stategy is called Last Write Wins (LWW) and is adopted by major paltforms like Cassandra. In reality, the skew in clocks could be much bigger which can cause problems like database writes mysteriously disappearing, independent nodes generating writes with same timestamp but conflicting values and the system not able to determine what transaction is actually more recent.

Although the clocks rarely misbehave, a robust software must be prepared to handle incorrect clocks. When a clock is out of sync and a little portion of our application relies on clocks, it might cause small data loses and can easily go unnoticed. But as the time passes the drift is going to get further and further from reality and can cause a catastrophe at some point. We must keep clocks in check and eliminate the nodes that have drifted from the cluster.

Byzantine Faults

The problem becomes much harder if the nodes are unreliable. So far we have been assuming the nodes will never lie. There might be a delay in response or no response at all. But if a response reaches to the node, it is considered that it’s the correct response (not faulty or corrupted). If a node claims to have received a particular message when in fact it didn’t. Such behaviour is known as byzantines fault and the inability of reaching consensus in this untrusting environment is known as Byzantines General Problem. In a system where all the nodes are owned by a single organisation and can be trusted, building a Byzantine fault tolerant system might not be a priority. However for a system with multiple organisations (peer-to-peer networks like blockchain), one or more participants may attempt to cheat or defraud others. In such cases it becomes absolutely crucial to have a system in place that assures that although the nodes don’t trust each other, they can still agree whether a transaction happened or not without having to rely on a central entity.

If distributed systems are to work, we must accept the fact that every component in our infrastructure can and will break at some point. Which means, in a large infrastructure something or the other is always broken. Our focus should be on building the fault-tolerant mechanism into the software which means the software should be able to handle the fault gracefully. Even for the smaller systems consisting of only few nodes. It is possible that something will become faulty someday and we as software engineers must know what behaviour to expect from the software in the case of fault.

I know, this blog talked about things going wrong in every possible way but hey don’t they say its always better to prepare for the worst and hope for the best? And lastly an amazing quote by Douglas Adams -

The major difference between a thing that might go wrong and a thing that cannot possibly go wrong is that when a thing that cannot possibly go wrong goes wrong it usually turns out to be impossible to get at or repair.